The Case Against Innocent People Talking to the Police

Imagine playing a game in which the stakes of the game are extremely high. Losing the game could result in loss of your job, rights, freedom, or ultimately your life. You’ve never played the game before.

The only rule you’re given is how to stop the game. When playing, you’re only limited to the information you personally possess. Finally, if you lie during the game (intentionally or inadvertently), you could be subject to additional punishment.

Your opponent is a trained professional and has played the game hundreds, if not thousands, of times. Your opponent knows the rules and can change the rules at any time. Your opponent has an entire team of individuals gathering information and all of the government’s resources at their disposal to assist them during the game. Finally, your opponent can lie and deceive you during the game, without any threat of punishment.

Knowing this, would you play the game? Of course not.

Answering Law Enforcement Questions

The game in question is answering questions from law enforcement. We get calls on a regular basis from clients asking whether they should cooperate with a police investigation. My answer is uniformly,

“No.”

As you can see below, it doesn’t matter if the client is guilty or innocent, my answer will always be a resounding, NO! To prove my point, I’m going to paint a hypothetical picture and specifically talk about the dangers of a police interrogation with 100% innocent people.

A Couple of Things to Remember

Before getting to the hypothetical situation, we must first get two truths out of the way.

First, police aren’t stopping random strangers off the street to ask if they want to meet at headquarters to ask questions about certain event. They just don’t.

There is a reason why they want to talk to you. Usually, it’s because they have evidence you committed the crime or they think you have information to get them closer to discovering who committed the crime. Either way, you are a potential suspect.

Second, you’ll never be able to talk yourself out of a charge. Many have tried, all have failed. If law enforcement obtains enough evidence against you, regardless of what you say, you will be charged.

A Hypothetical Situation

With that said, here’s our hypothetical situation:

Situation:

On April 1, 2019 in Lexington, KY there was a gang-style slaying resulting in one person’s death. It’s now been several months since the crime. There have been no arrests and the police are actively looking for suspects.

You receive a call from a local Detective asking you to come into headquarters to talk. The Detective is very nice over the phone and he tells you that he has information that you were present during the altercation, but he wants to clear your name. He doesn’t think that you did it, but he’s just doing his job.

You were always taught to tell the truth and obey authority figures, especially law enforcement. Your initial reaction is that you want to help law enforcement. Plus, you know that you didn’t do anything wrong.

You also don’t want the Detective to think that you have something to hide. You don’t want to get lawyers involved, because only guilty people need lawyers, right? Therefore, you agree.

Mistake #1: The Fifth Amendment is meant for Guilty AND Innocent People

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution states in relevant part,

“No person…shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.”

By agreeing to be interviewed by law enforcement you are voluntarily waiving your constitutional right against self-incrimination. This constitutional right is for everyone, regardless of guilt or innocence.

What the Supreme Court has Stated About Self-Incrimination

In the 1956 case of Ullman v. United States, a United States Supreme Court held,

“Too many, even those who should be better advised, view this privilege as a shelter for wrongdoers. They too readily assume that those who invoke it are either guilty of crime or commit perjury in claiming the privilege.”

More recently, in the 2001 case of Ohio v. Reiner, the United States Supreme Court held,

“We have emphasized that one of the Fifth Amendment’s basic functions … is to protect innocent men … who otherwise might be ensnared by ambiguous circumstances.”

While the Detective has you on the phone, he asks,

“Do you know the altercation I’m talking about?”

In which you respond,

“I don’t even own a gun.”

Mistake #2: Talking to the Police Always Gives Them Something They Can Use Against You

During this non-recorded phone call, the officer didn’t tell you that it was a shooting. While someone who read the news story may assume a shooting based on “gang-style slaying” the Detective didn’t specifically say a gun was involved.

While in Court, the prosecutor will ask,

“Did you notice anything odd when he answered your question by saying ‘I don’t even own a gun.’?”

The officer will respond,

“I did. There was no mention of a gun prior to him making that statement.”

Again, while on the non-recorded phone call, the Detective asks you,

“How do you know the victim?”

You respond by telling a long-winded story explaining how you and the victim went to school together, how the victim was always the most popular growing up, how he got all the girls, how he was the most athletic, how he used to pick on me some. You’ll conclude the story by discussing how you’ve since reconciled your differences and consider the victim a friend.

Mistake #3: Officer Doesn’t Recall Your Testimony 100%

During this non-recorded call, the officer can now take your statement out of context (mistakenly or inadvertently). When taken as a whole, everything that you said is honest, non-incriminating, and harmless.

However, because the conversation was not recorded, the officer may only remember that you stated he picked on you or that you were jealous of him growing up. Now the prosecutor has a motive. Then at trial, you’d be forced to combat that theory and present evidence about your good recent relationship with the victim.

Also, on the phone call, the officer asks you where you were on April 1st, 2019. You respond by giving the officer a description of your day’s events, including: stopping to get a cup of coffee then heading to Louisville for the day to visit family.

Once at headquarters, he leads you to a small room with a table and three chairs. The room is being recorded.

The Detective starts out friendly and asks some background questions about:

- where you live,

- how to spell your name

- where you are from

- phone number

- where you work

He also reads your Miranda Warning:

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.

After you agree to continue the questioning, the Detective asks you to repeat what you did on April 1st, 2019. You tell him about your morning, and you explain going to Louisville to see family, except this time, you neglect to mention you stopped for coffee.

Mistake #4: It’s Almost Impossible to Tell a Consistent Story

It’s hard for anyone to repeatedly tell the same story, without forgetting any details, while being completely 100% consistent. In this instance, neglecting to mention stopping for coffee can be a tool for the prosecution to show that you are lying. When the Detective testifies in court, he’ll say,

“He gave me inconsistent stories about his whereabouts. I thought that was very suspicious.”

You then give the Detective details about your time in Louisville. Again, you are telling the 100% truth. Unfortunately for you, an old classmate swears that they saw you at the scene in Lexington during the “gang-style slaying.”

Of course, the classmate is wrong, as you were in Louisville. However, due a false identification, the classmate has put you in Lexington in the middle of the altercation.

Mistake #5 – Police Can Use Your Truthful Statements Against You, If They Have Evidence (Mistaken or Unreliable) That Your Statements Are False

False identifications happen all the time. Honest, good people, wanting to seek justice, make mistakes. If you had chosen to invoke your Fifth Amendment right and remain silent, at trial it would be the old classmate’s recollection vs. your defense.

Unfortunately, since you gave the statement, at trial, it’s old classmate and Detective vs. your defense. Instead of focusing on whether or not you committed the crime, the jury is now focusing on how credible you are.

The officer now asks you what route you took to Louisville. It’s now been over four hours and you are exhausted, nervous, and have had to repeat your (true) story of being in Louisville and knowing nothing about the crime multiple times.

It’s been several months since that actual day. You’ve visited your family in Louisville several times since that day. You aren’t really sure what route you took to Louisville that day. But you want to sound truthful and cooperative so you respond by saying,

“I took Broadway to I-75 then got on I-64.”

However, that’s not true. You took Versailles Rd., turned on Frankfort Rd., then got onto I-64 because you stopped to get coffee at Starbucks. Little do you know the Detective already has traffic surveillance footage of you on Versailles Rd and you’re now caught in a proven lie.

Mistake #6: Filling in the Blanks or Getting Carried Away with the Story

Instead of saying that you didn’t remember, you made up an answer that the Detective can prove to be untruthful. You weren’t intending to lie. You were trying to be cooperative. But instead of relying on your memory (which often fades over time), you filled in the blanks.

The trained, skillful Detective now sees an opportunity to seize. It’s now been several hours and you’ve been peppered with questions. There’s been times when the Detective has walked out of the room, only to leave you sitting alone in a small room at the police headquarters in complete silence.

You are beaten down and are starting to second guess everything. All you want to do is go home. The Detective comes back in the room and says they have a recording of you at the scene. They tell you that there is cell phone video, cell phone location data, and building surveillance video that places you at the crime scene. The Detective then says,

“We already know he used to bully you, you must have hated that, I’m sure that kept eating at you. We also know that you were jealous of him growing up. He used to get the girls, he was the popular guy, and the most athletic. We also have a witness that saw you there. We know you did it, you’ve lied and lied to us all day, the judge isn’t going to like that. If you tell us the truth, we can help you – why did you do it?”

Tired, exhausted, nervous, and shaken, you respond by saying,

“I don’t know.”

Mistake #7: False Confession

The Detective now has a recorded confession. Even though it’s a false confession, the prosecutor can and will use it against you at trial. Of the 365 DNA exonerees to date by the Innocence Project, almost a third of those individuals gave false confessions, 28%.

Don’t Hesitate to Contact a Trusted Criminal Attorney

If you or a loved one are approached for questioning by law enforcement, please contact a knowledgeable criminal defense attorney immediately. While everyone has the right to remain silent, few choose to do so.

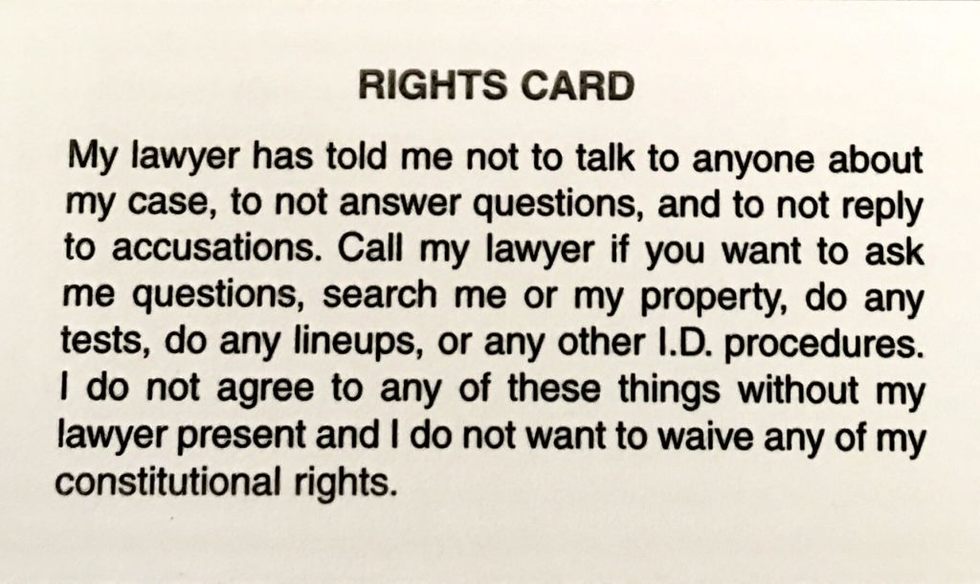

By invoking your right to remain silent and hiring an attorney immediately, you give yourself the best chance to avoid criminal charges completely. The earlier an attorney is retained, the more control you have over your difficult situation.

Even if your attorney is unable to prevent criminal charges from being filed, there are several benefits to retain an attorney pre-charge, including:

- Your attorney/private investigator can begin gathering helpful evidence and conducting witness interviews;

- Your attorney can negotiate with the prosecutor to issue a criminal summons, rather than an arrest warrant;

- In certain situations, your attorney can negotiate immunity for your cooperation;

- Your attorney can share beneficial information to investigations on your behalf, such as private polygraph tests or exculpatory evidence.

If you still haven’t been persuaded, take the advice of former United States Supreme Court Justice, United States Attorney General, United Solicitor General, and Chief Prosecutor at the Nuremburg Trials, Justice Robert H. Jackson:

“Any lawyer worth his salt will tell [a] suspect in no uncertain terms to make no statement to police under any circumstances.”